Ghost in the Shell is a series of Japanese animated movies (anime,アニメ) featuring cyborgs (“cybernetic organism”, in this case a human with both organic and robotic body parts). I was struck by the frequent references to puppets in several of the movies, and I want to explore the symbolism behind this. I will look in particular at the movies “Ghost in the Shell”, “Innocence” and “Solid State Society”, because in these movies the references are most clear. Familiarity with the movies is not required.

Puppets, dolls, marionettes, mannequins

I use the word puppet as the most general word. A doll to my mind is a puppet used as a child’s toy. A marionette is a puppet with strings to manipulate it. And a mannequin is a puppet in the sense that it is a representation of a human. I would say that the crucial property is that a puppet is somewhat articulated or can be made to move.

In Japanese there are also several words for puppets and dolls. The most common word is ningyō, 人形 , “doll, puppet”. The word nin means person and gyō means form, shape. Specifically, ayatsuriningyō, 操り人形, sometimes shortened to just ayatsuri, 操り, means a puppet controlled by an operator, e.g. a marionette. The word ayatsuri means “manipulation”. The other word that is used in Ghost in the Shell is kairai or kugutsu, 傀儡, this is an older word and not so common (neither of the kanji is in common use). It is an interesting word because both its characters mean “puppet”. The first, 傀, is composed of “person” and “ghost”; the second is likely simply a variant, and is only used in this word. The reading kugutsu apparently derives from kugu, 久具, a plant from which the baskets were woven that were used to transport the puppets by itinerant puppet players.

Cyberbrains and ghosts

In the Ghost in the Shell series, one of the main themes that is being explored is what defines a human. A cyborg is a human with all or parts of its body replaced by artificial components. In the Ghost in the Shell universe, even the brain can be treated this way, being augmented by a cyberbrain (dennō,電脳), essentially an electronic system with a similar functionality, but connected to the net). In the most extreme case, the entire human brain is replaced by a cyberbrain which contains the content of the original human brain. By contrast, robots do not start out human. The difference between a robot and a full-cyborg human is only the origin of the data in the brain. In Ghost in the Shell, the word ghost is colloquial slang for an individual’s consciousness or soul, which is what sets it apart from a robot.

Part of the plot of the second movie, “Innocence”, is that robots get a ghost through a process called “ghost dubbing”, i.e. copying the ghost from a human and putting it into the robot cyberbrain. This idea returns in the recent “Arise” series.

A brief note on the characters

In this article I will mention a few characters from the series who belong to a kind of special state intelligence unit called “Public Security Section 9” (公安9課):

- “The Major”, Motoko Kusanagi, a female cyborg, the main character in the series.

- Batō, a male cyborg, the protagonist in “Innocence”.

- Togusa, a human with a cyberbrain, the companion of Batō in “Innocence”.

Furthermore, I mention a character from “The Individual Eleven” series, Hideo Kuze, a male cyborg, a very charismatic revolutionary.

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

In the first Ghost in the Shell movie, there is no strong symbolism of puppets, but there are several references.

Project 2501 is a program that can stealthily manipulate politics and intelligence, altering databases and the memories in people’s cyberbrains. While traversing the net as it performed its tasks, Project 2501 acquired and processed so much information that it eventually achieved self-awareness. Its creators regarded this as a bug in the program. When Project 2501 realised that its programmers would try to kill it when they discovered it had become sentient, it devised a plan to ensure its own safety.

When the manipulations of Project 2501 are discovered, they are initially assumed to be the work of an extremely skilled hacker, nicknamed the Puppet Master (人形使い,ningyoutsukai), presumably because it is a master manipulator and the people whose cyberbrains are hacked become effectively sock puppets.

It is worth nothing that at the end of the movie, Project 2501 is assimilated into the cyberbrain of Motoko Kusanagi. So from a certain angle Kusanagi becomes the Puppet Master.

A more oblique but to my mind more important puppet reference is the scene where Motoko Kusanagi rides on a passenger boat on the canals of Hong Kong. This is a long montage without dialogue. Kusanagi sees someone very much like herself at a table in a restaurant. Is it a human or a cyborg? She also looks at some mannequins in a shop window, and the scene ends with an empty shop with undressed, partially disassembled mannequins. You can’t help but think about how she must see a parallel between herself and these puppets.

Innocence (2004)

The second Ghost in the Shell movie, “Innocence”, is where the puppet symbolism is present most strongly.

The main reference to puppets in Ghost in the Shell “Innocence” is an implicit one: the title song is called the Puppet Song, of which I wrote in an earlier article. The full title of the song is kugutsu-uta: uramite chiru (傀儡謡「怨恨みて 散る」, くぐつうた「うらみてちる」) which means “Puppet song: The flowers resentfully fall”. The theme of the song is mortality. It is used a few times in the movie, but most prominently in the opening scene, which shows the creation of a humanoid robot, and in the parade scene, which is based on a Taiwanese Buddhist temple procession and involves giant puppet-like figures.

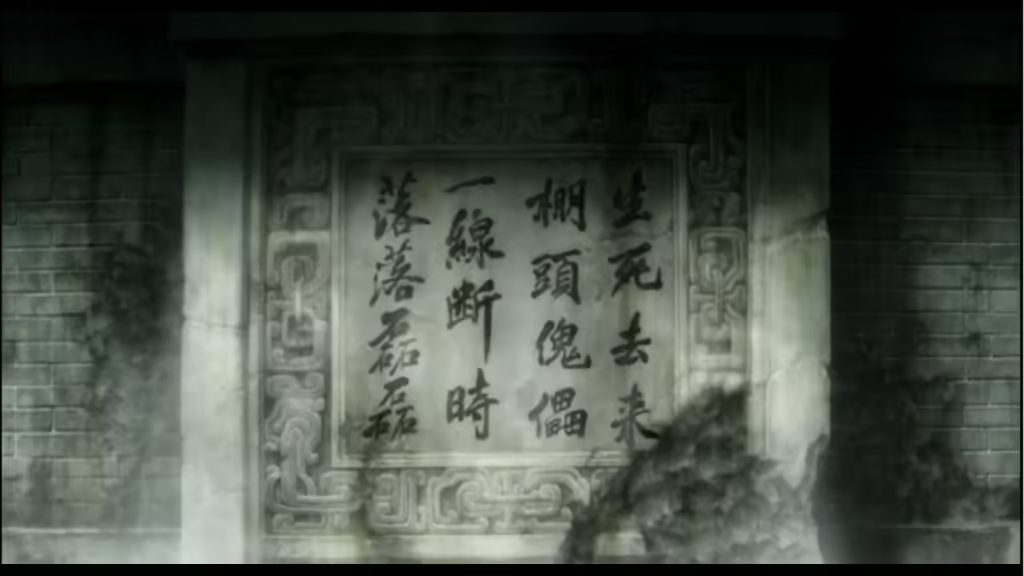

There is another reference, one that I found particularly interesting. After the parade scene, Togusa sees the following poem written on a wall:

生死去来

棚頭傀儡

一線断時

落落磊磊

The writing order is top to bottom, right to left, and it is an archaic and poetic form of Japanese without hiragana. Togusa reads it in full as:

生死の去来するは、

棚頭の傀儡たり。

一線断ゆる時、

落落磊磊。

せいしのきょらいするは、

ほうとうのかいらいたり、<b

いっせんたゆるとき、

らくらくらいらい

seishi no kyorai suru wa,

hōtō no kairai tari,

issen tayuru toki,

rakuraku rairai.

In the dubbed version, this is translated as:

“Life and death come and go

like marionettes dancing on a table.

Once their strings are cut,

they easily crumble.”

The rakuraku rairai is particularly poetic. raku means to fall down; rai means a heap of stones, the kanji 磊 is stone 石 repeated three times. Hence the overall meaning of crumble. Curiously, the word 磊磊落落 (rairairakuraku) also exists; it means “openhearted; unaffected; free and easy”.

The original author of this poem is a Buddhist monk called Getsuan Soukou (月庵宗光), who lived 1326-1389, during the The Nanboku-chō period (南北朝時代). He used it in one of his sermons. The poem got included in a famous treatise on Noh theatre, “A Mirror of the Flower” (Kakyō, 花鏡) by Zeami Motokiyo (世阿弥 元清) (1363–1443), who was the son of Kan’ami Kiyotsugu. Together they are considered the founders of Noh.

Noh theatre is a form of classical Japanese theatre with music, poetry and dance. It is still regularly performed today, and has a similar status to opera in Western society. In Ghost in the Shell there are occasional references to Noh, in particular in “The Individual Eleven” where Hideo Kuze has a lengthy monologue about the origins of Noh and how it was cherished by the samurai class.

Zeami’s work “A Mirror of the Flower” deals amongst other topics with the link between marionettes and Noh theatre actors. The work has been translated into English (and you can read it for free) and I found in it a closer (and perhaps better) translation of the poem:

“Birth and death, goings and comings:

A marionette in play.

When one string snaps,

It falls and collapses.”

The comment by Zeami is quite interesting:

“This [poem] exemplifies the condition of humans who act out the cycle of birth-and-death. Although the manipulation of an artificial figure upon the boards [of a puppet stage] may [make it] appear as all sorts of things, it is not really an object that moves [of its own will]. It is [the result of] the play of manipulated strings. Cut these strings and it collapses – such is the spirit [of this poem].”

There is also an interesting footnote:

“This poem appears in Gettan Osho Hogo (月庵和尚法語,’[Rinzai Zen] Priest Gettan’s Talks on Buddhist Principles’), a late 14th-century text. Zeami’s subsequent interpretation of the poem as descriptive of the relation between the actor’s mind and the ‘illusion’ of character that it creates differs from the Zen intent of the poem, which admonishes the reader to break free from the trap of the illusory world of ‘birth-and-death’.”

But considering the argument presented before the poem, what Zeami means is that as soon as the actor loses this ultimate state of awareness, the acting will collapse. Zeami argues that when the actor achieves the ultimate state of awareness, he realizes how his mind can be used to create the illusion of reality that he presents to his audience with a detachment and skill associated with a master puppeteer. In other words, the actor on the stage is the puppet manipulated by the actor’s mind.

This is a very powerful concept, and closely related to the type of Buddhist meditation that focuses on existing in the moment. It is likely also why Noh appealed to the samurai. Within the context of Ghost in the Shell, this concept gets an extended meaning, not restricted to the mind and body of a human. Any self-aware entity controlling a humanoid form can be considered in this way.

The question is why this poem figures so prominently in the movie, but specifically in the scenes to do with the place where the robots are created (Etorofu, one of the Kuril Islands). The two main characters, Batō and Togusa, go there to interview a powerful hacker, Kim, who is obsessed with dolls and clockwork and who has transfered his own ghost into a puppet-like robot. Clearly, Kim is the one fascinated by this poem, as every appearance of it is connected to him.

Generalizing Zeami’s view of the poem, I am inclined to interpret the strings in the poem as the connection between the robots and the mind that controls them. In a key scene, the protagonist Batō enters the factory ship where the robots are made. He is attacked by an army of robots programmed remotely to fight him. Motoko Kusanagi hacks one of them and downloads her ghost into it, and fights on his side. She then gains control of the ship’s central computer, at which point all the robots except the one she controls collapse: their threads have been cut. This is a recurrent theme in Ghost in the Shell, for example in “Solid State Society” something very similar happens.

But perhaps more significant is the fact that to Batō, who clearly has missed the Major deeply since she disappeared at the end of the first movie, three years ago, immediately identifies the robot with her. As the robots on the ship are not dressed, he puts his jacket on her. And this despite the fact that the robot has no facial expression and looks identical to the others. When the Major disconnects from the robot, it also collapses. But Batō now knows that the ghost of the Major is always around.

And as if not to leave any doubt about the importance of the puppets in the movie, the final scene ends with a close-up of a doll held by Togusa’s daughter.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – Solid State Society (2006)

Right at the start of this third movie, there is a reference to “the Puppet Master”. The Major listens in to a conversation where the nickname is used, and comments “The Puppet Master? Not a bad name!”. Note that in Japanese the word is different from in the first movie: instead of ningyōtsukai 人形遣い it is kugutsumawashi 傀儡廻; kugutsu is a different reading for kairai, 傀儡, the word for puppet used in the poem in Innocence. The word mawashi, 廻, means “to go around”, and kugutsumawashi refers to wandering puppet players who went from village to village. Because of the different word choice, it is in the original Japanese version less obvious that there could be a link with the Puppet Master in the first movie.There is a however a clear link with the second movie because of the word kugutsu, which is lost in the English version.

As in the first movie, the initial assumption is that this Puppet Master must be some top-wizard-level hacker (超ウィザード級ハッカー); then the suspicion grows that it might be some distributed program which might have achieved some degree of self-awareness. But considering the first movie, it should come as no surprise that there is a connection with the Major.

Early on we see the Major operating many different cyber bodies remotely, even several at once. At one point, she tries to control one too many and one of them collapses, and she remarks:

同時に義体を操るのは、2体迄が限界ね

tōji ni gitai wo ayatsuru no wa, nitai made ga genkai ne

The English subtitles say “Controlling two prosthetic bodies at the same time is apparently my limit”. The word gitai,義体, is closer translated as cyber body; the word used for controlling is ayatsuru,操る, exactly the word for manipulating a puppet. And there is a scene where one of the Major’s remote cyber bodies deactivates during a conversation, leading the person talking to it to comment, “Huh, that’s a puppet as well?”.

Bonus: stills of the puppet poem in “Innocence”

The first occurrence of the poem is after the parade scene:

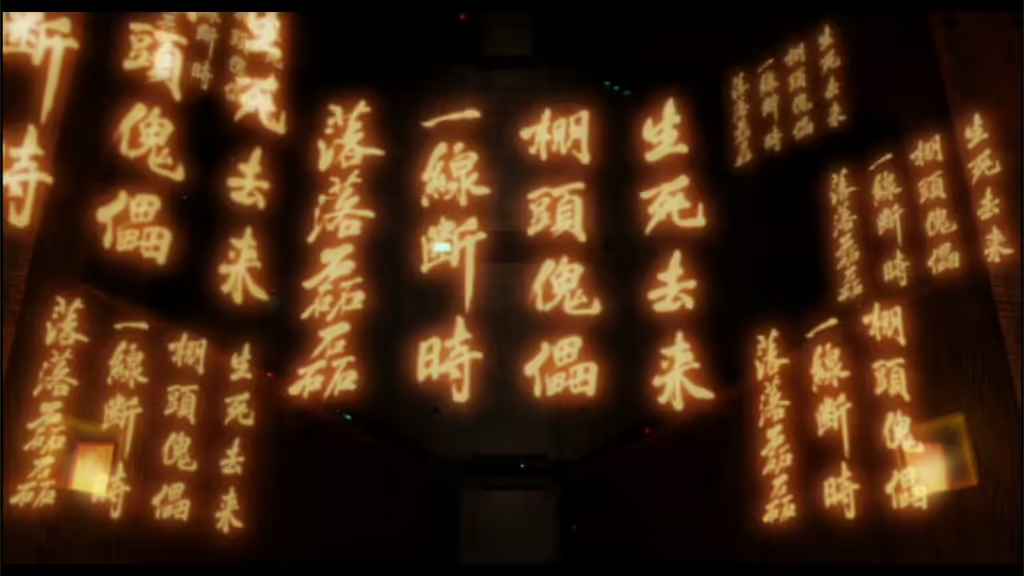

It also appears on the wall of Kim’s study:

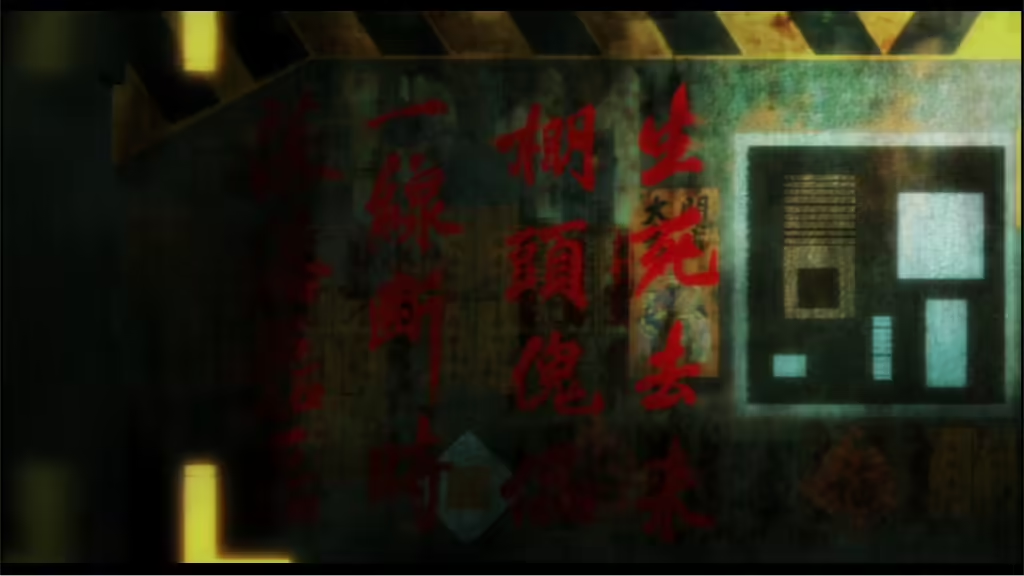

After Togusa narrowly escapes an attack on his cyberbrain :

When Batō and the Major manage to take control of the factory ship:

Further reading

- Free: Filimon, Luiza Maria. “Dolls, Offsprings, and Automata. Analyzing the Posthuman Experience in Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence.” Ekphrasis. Images, Cinema, Theory, Media 17.1 (2017): 45-66.

-

_The banner picture shows a white plastic head wearing a samurai helmet, all of it made from junk plastic_