One of my favourite movies is Wong Kar-Wai’s movie “In the mood for love”, from 2000. It’s set in Hong Kong in the early 1960s, almost all scenes are at night and it rains a lot. It’s a tale of love and unfaithfulness.

Is it basically a love story about these two characters? Finally I think it’s more than that. It’s about the end of a period. 1966 marks a turning point in Hong Kong’s history. The Cultural Revolution in the mainland had lots of knock-on effects, and forced Hong Kong people to think hard about their future. Many of them had come from China in the late 40s, they’d had nearly 20 years of relative tranquillity, they’d built themselves new lives – and suddenly they began to feel they’d have to move on again. So 1966 is the end of something and the beginning of something else.

A lot has been written about this movie, reviews, essays, in -depth analysis of what makes it so special. I want to talk about a novel a and a song that are closely tied to the movie. And about the drawings of course.

A novel

The movie has intertitles at the start and the end:

It is a restless moment. She has kept her head lowered, to give him a chance to come closer. But he could not, for lack of courage. She turns and walks away.

That era has passed. He remembers those vanished years.

Nothing that belonged to it exists any more. As though looking through a dusty window pane, The past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

This is adapted from novella “Duidao” (“Intersection”) by Liu Yichang. Wong Kar-Wai says:

The first work by Liu Yichang I read was Duidao. The title is a Chinese translation of tête-bêche, which describes stamps that are printed top to bottom facing each other. Duidao centres round the intersection of two parallel stories – of an old man and a young girl. One is about memories, the other anticipation. To me, tête-bêche is more than a term for stamps or intersection of stories. It can be the intersection of light and colour, silence and tears. Tête-bêche can also be the intersection of time: for instance, youthful eyes on an ageing face, borrowed words on revisited dreams. Or a novel published in 1972, a movie released in 2000, both intersecting to become a story of the ’60s.

In her essay “In The Mood for love: intersections of Hong Kong modernity”, Audrey Yue summarises the novel as follows:

Set in 1970s Hong Kong, Duidao tells the parallel stories of Chunyu Bai, an old reporter from Shanghai who fled to Hong Kong in the 1940s to escape the Japanese Occupation, and Ah Xing, a young single woman who lives with her parents.

Bai is nostalgic, fuelled by his memories of Shanghai, his youthful liaisons with dancehall girls and his failed marriage. Ah Xing is forward-looking. Always day-dreaming about herself as a famous singer or a movie star, she longs to find love and marry a handsome husband, someone ‘a bit like Ke Junxiong, a bit like Deng Guangrong, a bit like Bruce Lee, and a bit like Alain Delon’.

Triggered by songs, old photographs, and magazine covers and posters of movie stars, the two characters’ temporalities are retrospective and projective. In the story, they only meet once sitting next to each other in a crowded cinema.

Everyday practices like walking, commuting, listening to music, watching television and going to the movies highlight their close encounters. These practices construct Hong Kong, already a Chinese migrant enclave and a metropolis dizzy with escalating property prices and swirling in the popular media mix of Taiwanese Mandarin pop songs, Filipino renditions of American Top Ten hits, Hollywood cinema and French film icons.

A song

The title of the movie, 花樣年華, Fa Yeung Nin Wa in Cantonese transliteration, is taken form a 1940s song Hua Yang De Nian Hua (花樣的年華) “Age of Bloom” by famous 1940s singer Zhou Xuan. It is this song that Mr. Chan, on business Japan, requests to be played for his wife’s birthday. It’s a melancholy song talking about a happy past that is no longer, and it can also easily be interpreted as a reference to the Japanese occupation.

The song was released after the war, in 1947, as part of the movie “Sauvignon Blanc”. But there is a reference to a solitary island, and a period of gloom and yearning for the homeland.

The period between the start of the Battle of Shanghai in August of 1937 and the outbreak of the Pacific War in late 1941 is known as the Solitary Island Period. During this time, the International Settlement and French Concession in Shanghai were not occupied by the Japanese but the rest of the city was occupied. The film makers who remained worked in these foreign concessions. There is an interesting article about Zhou Xuan that provides more context about the Shanghai movie scene in the 1930s and 1940s.

The writer of the song, Fan Yanqiao, worked for one of those film companies. Likely he used his recollection of that time as inspiration. (He also wrote the original script for “Sauvignon Blanc”, called “Flowers Bloom In Streets”.) The composer of the song is Chen Gexin, under the pseudonym Lin Mei. He wrote this song in Hong-Kong during a brief happy period in his life.

Wong Kar-Wai also made a short film, named Hua Yang De Nian Hua, after the track, consisting of short scenes of movies of that era, with the song as soundtrack. Clearly he considered the song and its background important.

I found this translation of the song’s lyrics:

Age of bloom, spirits like the Moon

A crystal mind like ice and snow

Such a beautiful life, such an adoring couple

A family so whole and complete

Suddenly this lone-standing island,

Is covered by shattered mist and sorrowful rain

Shattered mist and sorrowful rain

Ah, my beloved homeland

When can I return to your warm embrace?

When will the mist and cloud be dispelled

And release your fogged light?

Age of bloom, spirits like the Moon

And another one, with a contemporary performance.

We are young, like blooming flowers

We are fresh, like the shining moon

We are sharp, like ice and snow.

We have a beautiful life, tender lovers and happy families.

But suddenly this lonely island is shrouded in a miserable foggy gloom. A miserable foggy gloom.

Ah! My dear motherland, when can we return to your arms?

When will the dark clouds and fog disperse?

When will we see the light again?

We are young, like blooming flowers

We are fresh, like the shining moon.

The original lyrics in traditional characters (as were used at the time of its release):

花樣的年華

主唱:周璇

作詞:范煙橋 作曲:林枚

花樣的年華,月樣的精神,

冰雪樣的聰明。

美麗的生活,多情的眷屬,

圓滿的家庭。

驀地裡這孤島籠罩著

慘霧愁雲,慘霧愁雲。

啊!可愛的祖國

幾時我能夠投進你的懷抱,

能見那霧消雲散,重見你放出光明。

花樣的年華,月樣的精神。

and the transcription:

Hua yang de nianhua yue yang de jingshen

Bingxue yang de congming

Meili de shenghuo duoqing de juanshu

Yuanman de jiating

Mo di li zhe gudao longzhao zhe

Can wu chou yu, can wu chou yu

A ke ai de zu guo

Ji shi wo nenggou kaojin ni de huaibao

Neng jian na wu xiao yun san

Chong jian ni fang chu guangming

Hua yang de nianhua yue yang de jingshen

The drawings

I made two drawings from scenes of the movie, a smaller one in Chinese ink and a larger one in Conté pencils.

The stair scene

I made a drawing of what is probably my favourite scene in Wong Kar-Wai’s movie “In the mood for love”. The protagonists, Su Li-zhen (“Mrs. Chan”) played by Maggie Cheung Man-yuk and Chow Mo-wan played (“Mr. Chow”) by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, pass each other by on a dark, narrow staircase. They steal a glance at each other and the scene is very evocative. All the time I was working on it, Shigeru Umebayashi’s beautiful music “Yumeji’s Theme”, which accompanies the scene, was playing in my head.

I did the drawing on Schoellershammer watercolour paper, 30x40 cm, 250g/m², with the Chinese ink I wrote about a while ago, and two Chinese brushes. The ink is excellent but the paper and the brushes are not great. As a result, there is a lack of control that I find interesting.

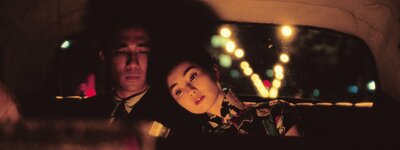

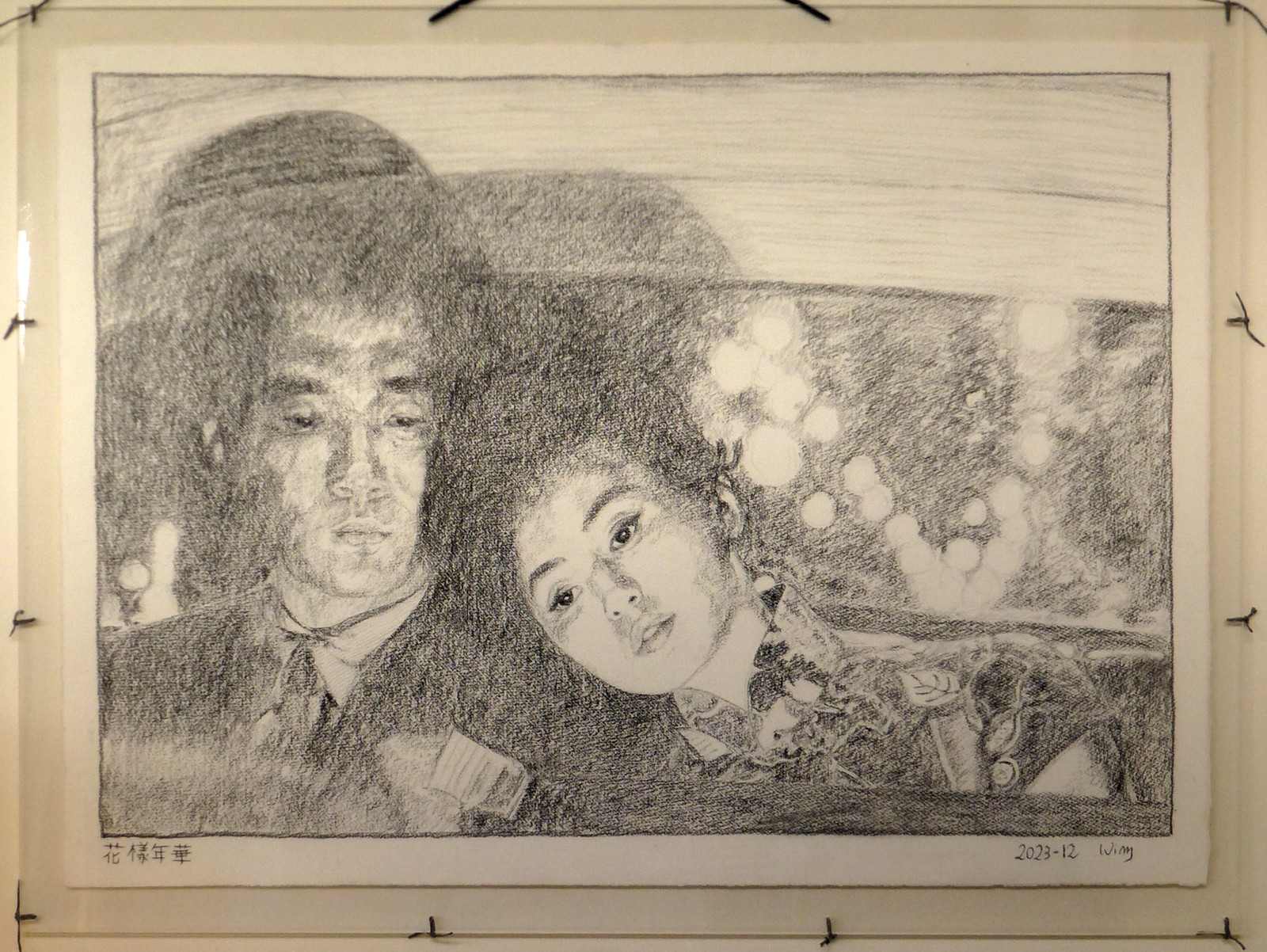

The taxi scene

In another, the couple is together in a taxi, after Mr. Chow has told Mrs. Chan of his intention to move to Singapore. I think the expressions on their faces are very evocative of their complex feelings. It’s just before we hear Mrs. Chan’s off-screen voice saying, “I don’t want to go home tonight.” That’s the scene I wanted to draw.

I wanted to create a double portrait of this couple who are, as a BFI critic put it “ordinary mortals made movie-star beautiful by love”, and I stayed very close to the original shot, apart from cropping it to get both faces in an optimal position.

I used my preferred rough watercolour paper (Fabriano Artistico, 300 gsm, NOT), about 50 cm x 70 cm. I set up the drawing in ordinary pencil and then added tone with Conté pencils (from HB to 3B). Because the paper has such a rough grain, the pencils can’t fill the hollows in it, and I took care not to smudge the strokes. The effect is therefore not a deep, intense black but something more pointillist.

The banner is a crop of the still on which the drawing is based.