I would like to tell a little story. I have always liked drawing, and sometimes I use ink and brush. Long ago and far away, in a country over the sea, a fellow PhD student from China made me present of an inkstone. It came in a box with a damasked cloth sleeve which opened like a book. The box itself was covered in bright cerulean fabric and inside it, the stone was cushioned in pink silk.

But it is not of the box that I want to talk, beautiful though it is, nor of the stone itself; nor do I want to talk about the inkstick that was enclosed in that same box. It was decorated with a picture of a bird of paradise on a tree with blossoms, all in gold, and it was so pretty I never could bring myself to use it.

But with the box came also three additional inksticks, each in its unassuming but stylish cloth-covered small cardboard box, with a white paper label covered in Chinese characters pasted on the top. I couldn’t read them then, and I did not pay much attention; but I noticed that, though the characters where the same on each label, the labels where nonetheless individual.

These inksticks are also very pretty, with a rustic river scene on one side and calligraphy on the other. But more on that later.

A few days ago, I was making a brush drawing using one of these inksticks, and I happened to look a bit closer at the other markings. On the top it says “油煙一〇一” and on the narrow side “上海墨廠出品”. That means “lampblack 101” and “made by the Shanghai Ink Factory”. I wanted to know more about the meaning of the “101”. And thereby hangs a tale.

The history

At the start of the Qing dynasty (1636), there lived in Shè Xiàn, Ānhuī province, a master ink maker and artist called Cao Sugong 曹素功 (1615–1689).

In the sixth year of the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1667), he founded the Cao Sugong Ink Factory. Two hundred years later — yet still in the Qing dynasty, in the third year of the reign of the Tongzhi Emperor (1864) — the business moved to Shanghai. It gained a high reputation for the excellence of its ink and won numerous international prizes.

The Cao Sugong factory produced four grades of ink: 五石漆烟, 超貢烟, 貢烟, 頂烟, meaning “five minerals (wǔshí) lacquer soot”, “super tribute soot”, “tribute soot”, “top soot”. The grade 五石漆烟 marked the highest quality.

However, in 1966, at the start of the Cultural Revolution, one of the most notorious campaigns was the Four Old Things campaign. The Four Old Things were: Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Customs, and Old Habits (jiù sīxiǎng 旧思想, jiù wénhuà 旧文化, jiù fēngsú 旧风俗, and jiù xíguàn 旧习惯). Characters like “貢” (tribute), with their feudal associations, became unacceptable, and so the grades were renamed to lampblack 101, 102, 103 and 104. In Chinese, lampblack 101 is written “油煙一〇一”, the marking on the top of my inkstick.

Furthermore, the Cao Sugong company was combined with several other ink factories and became the “Shanghai Ink Factory”, “上海墨廠”.

After the Cultural Revolution, in the 1980s, the Shanghai Ink Factory changed its name back to “Cao Sugong” and the use of the old grades was also reinstated.

I got these inksticks in 1992, long after this change back to the old the branding and grading. That means that they were then probably already quite rare items, as the factory only operated as Shanghai Ink Factory for about 20 years in its long and illustrious history.

I don’t know for how long these stick were out of production. However, today there are again inksticks sold that look exactly like mine, also labelled “油煙一〇一” (lampblack 101) and “上海墨廠出品” (made by the Shanghai Ink Factory), and these are high-quality items, used by professional ink artists. Like the ones I have, they are not intended for export.

These new “101” inksticks are made by the current incarnation of Cao Sugong, after its fusion with famous brush maker Zhou Huchen 周虎臣. Clearly, this particular product has a very high reputation in China, which makes it worthwhile for the company to produce it again, with the original grading and branding from the Shanghai Ink Factory era.

The making

Did I mention that, when you grind this ink on the inkstone, it produces a very pleasant smell?

Making an inkstick requires several steps: the lampblack is refined, mixed with glue and other ingredients. To improve the fragrance, lustre and insect resistance of the inksticks, more than 20 kinds of Chinese medicinal herbs are added, along with gold leaf. The ingredients are mixed by pounding the ingredients with an eight-pound hammer and is very tiring work. Lu Jianqing, the now-retired director of Cao Sugong recalls how, as an apprentice, having to do this thousands of times a day, he couldn’t lift his hand the next day.

They are then kneaded by hand, and finally pressed into a wooden mold. This mold is carved with a picture on one side and a related piece of calligraphy on the other. The stick is dried, gold leaf is applied and the decorations are painted on. The process requires four kinds of artists: the ink maker, the carver, the calligrapher and the painter.

Cao Sugong inksticks come in three standardised weights: 1 liang (31 g), like the ones I have; 2 liang and 4 liang. The small sticks need to be dried in the shade for six to eight months; the largest ones require up to two years of drying. During the drying period, they need to turned by hand every day because otherwise they would bend out of shape. The whole process is still very artisanal.

The poetry

The picture on my inkstick shows a bucolic scene along a river.

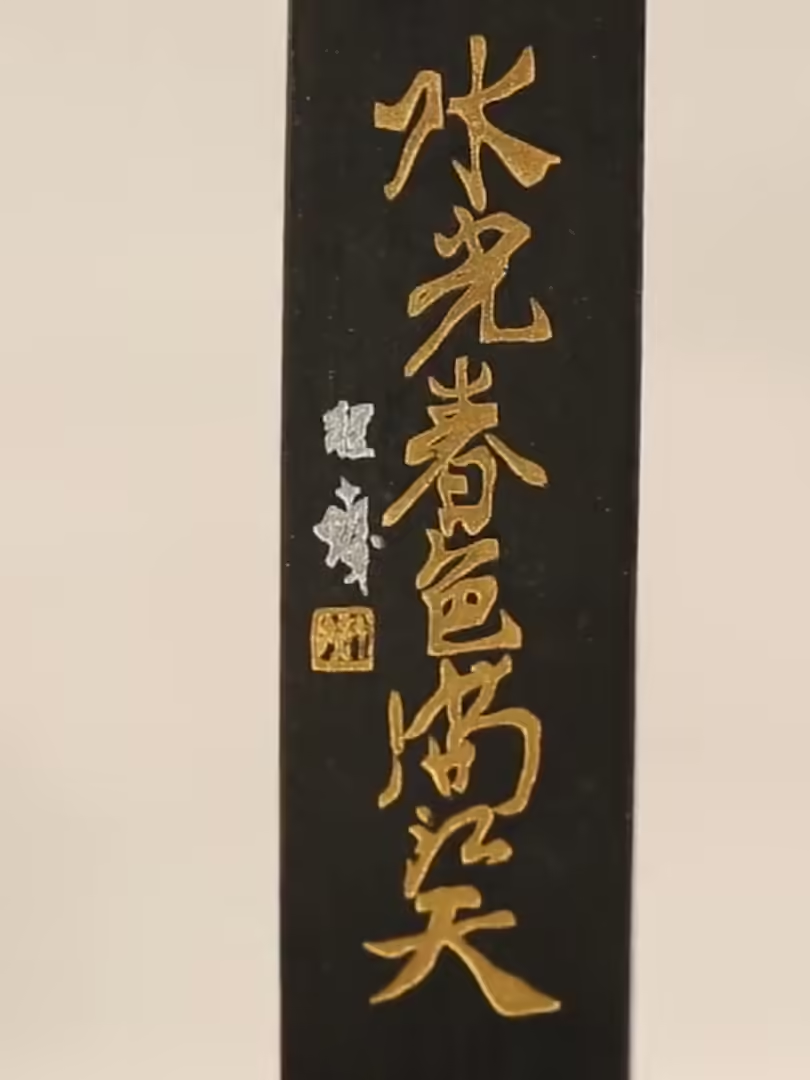

It also has some beautiful calligraphy. I have always been fascinated by Chinese characters, and one day I hope to study Chinese. Not that it would help me with this text, as it is in ancient Chinese.

The characters read

水光春色滿江天

At first, I could not find a proper translation, but based on a literal reading of the characters, I interpreted it as

river and sky, full of spring colours, light on the water

This is the first line of the poem “江南行”, which means “South across the river”. The poem was written during the Tang dynasty (around 831 CE) by the poet Chen Biao (陈标, or 陳票 in traditional characters). Only twelve of his poems are known to exist, but he must once have been a famous poet, as some of his poems are included in the “Shinpenshū”, a collection of poems compiled by the monks of the Kennin-ji temple in Kyoto in the 15th century.

Today, he is not well-known at all, which makes the choice of the poem on the inkstick intriguing. It is likely the influence of the artists and calligraphers of the “Chinese Painting Research Academy” (中国画研究院), created in 1981, who worked closely with the Shanghai Ink Factory.

This is the poem in full (in traditional characters):

水光春色滿江天,蘋葉風吹荷葉錢。

香蟻翠旗臨岸市,艷娥紅袖渡江船。

曉驚白鷺聯翩雪,浪蹙青茭瀲灩煙。

不怕江洲芳草暮,待將秋興折湖蓮。

I asked on the Fediverse if anyone could provide a translation, and the inimitable L.J. rose to the challenge to produce the following amazing poem:

South Across the River

The water-light and hues of spring

lap up to vaulting blueWhile winds brush lily pads weighed down

with drops like coins aglow.Blue flags and toxicating dregs

descend on city shoreSuch luscious sweetness clad in red

across the river rowed.Egrets affrighted by the dawn

flock on and on like snowThe rolling waves and fodder green

like swelling smoke o’erflow.Be not afraid that virtue high

will quite desert JiangzhouAwait the autumn days when we

will pluck the lotus blow.

Translation by L. J. Lee with suggestions from Zoë Camille and cynth

And on that wonderfully poetic note I conclude my story of the inksticks from the Shanghai Ink Factory.

The background

This little story is a patchwork pieced together from a large number of sources brought up by a deep trawl through the net. Here are the most interesting of them:

- My starting point was the blog of an ink shop in Osaka (in Japanese), which has an article on the 101 grade and on the history of the Shanghai Ink Factory.

- I found an articles about the history of the Cao Sugong ink shop and about the making of the inksticks.

- I found a video on Youtube, with English subtitles, about the way inksticks are made at Cao Sugong. The person in the video, Lu Jianqing, started working at the company in 1978 as an apprentice, and became the director in 1989, so he might very well have been involved in the making of my inksticks.

- There is also an article with great pictures about a different ink factory.

- This is the site selling copies of my inkstick, there is a nice promo video.

- This site has the full text of the poem.