In early 2011, as a result of a press release about my work, a researcher from Japan contacted me and proposed a research collaboration. I had always been very interested in Japan, so this was a great opportunity. I started planning a research visit, and at that point I thought it would be better to learn some Japanese. So about three months before the trip I started my first Japanese lesson.

Fortunately, nobody told me one should not attempt to learn a new language over the age of forty. And anyone who has learned some Japanese will appreciate how ridiculously short a time three months is; luckily I didn’t know any better.

In any case, I started learning very basic Japanese and I loved it: the writing system, the grammar, the culture as expressed through the language. Learning your first kanji (Chinese characters used in Japanese) is a great experience, because kanji are mysterious, beautiful and concise – and you think you can see the logic to it. And learning the first phrases makes you feel it won’t be all that hard. It’s wonderful.

Because of the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, I had to postpone my trip. But in the summer of 2012, having learned Japanese for a bit more than a year, I went to Kyoto for a two-month research visit.

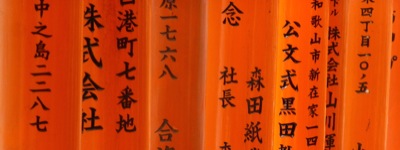

And it was amazing: kanji everywhere! Somewhere along the path, learning Japanese had become a goal in its own right, not just a practical tool for survival in the wild. It was that as well, of course – just try shopping in a Japanese supermarket without knowing any Japanese.

So I conversed in broken Japanese, and looked up kanji on my phone (and was surprised how many signs said “dentist”), and tried to improve my hiragana and katakana reading skills. I didn’t actively study, the total immersion was all I wanted.

At that time I had learned only basic grammar and sentence structure, very little informal Japanese – my teacher does not hold with that – and about 100 of the 500 most frequent kanji. I quickly discovered that “most frequent” does not really mean “common” or vice versa. The “most frequent kanji” list is based on newspaper articles, so there are many common kanji that are not in that list. Also, “knowing” or “having learned” a kanji is a rather vague term, and being able to tick them off in a spaced repetition app like Anki or Memrise (great tools though they are!) does not mean you know the meaning of a word consisting of “known” kanji, let alone its pronunciation.

Kanji typically have several meanings, sometimes wildly different (e.g. 洗 means both “wash” and “inquire into”) and several readings, some based on the original Chinese pronunciation of the character, some on the Japanese pronunciation of the meaning of the character (e.g. 明日 “tomorrow” can be read as “ashita”, “asu” or “myonichi”). So there is a lot to learn.

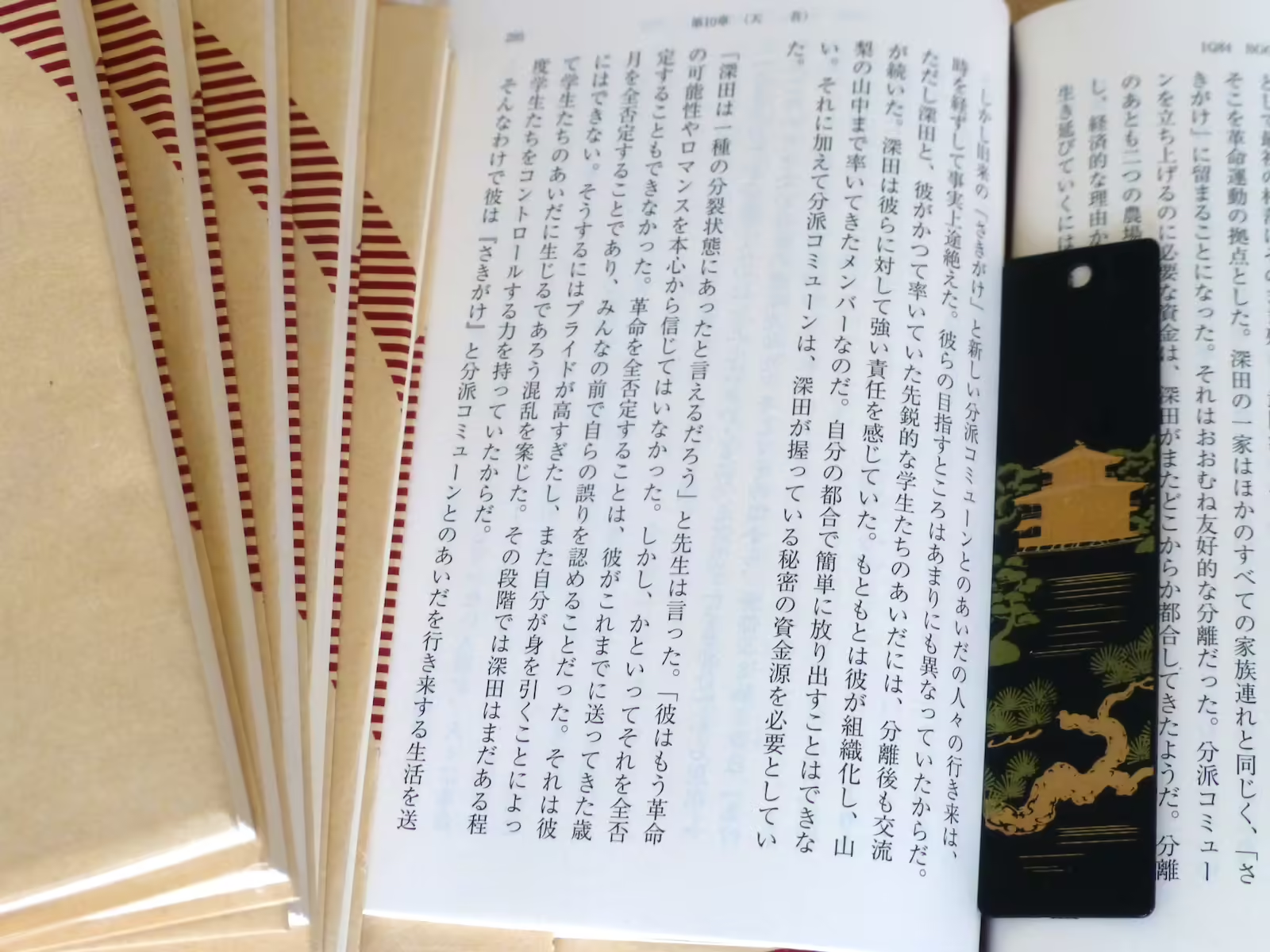

By now I was hooked, by both the language and the country. Two more years of study later I visited Japan again. On that visit I bought the paperback version of Haruki Murakami’s “1Q84”. It comes in 6 volumes, each about 400 pages.

I started reading it on my return (October 2014). It is a slow process because really my Japanese is by far not good enough. I continuously encounter kanji that I have not learned yet or already forgotten, so I have to look them up. Luckily I can do this on my phone, by writing them stroke by stroke. It is now April 2016 and I have reached page 295 (of 357) in the first volume. At this rate, it will take me another 15 years to finish the book. This may not seem very encouraging. However, I hope of course that my reading skills will improve. And in fact I have found reading this way to be more enjoyable than reading the book in English translation: reading Japanese requires a deeper concentration and I feel more immersed in the story – and I find the Japanese writing simply beautiful.

The books have also inspired me to make a few “Murakami meals”, which I’ll be posting soon. Speaking of food, I also bought a Zen temple cuisine cookbook, available in Japanese only. It gives a unique insight in the Zen way of cooking – and the language and vocabulary are much easier than Murakami’s.

- I’d like to thank my teacher Rie Ogura for her patience with me, waiting endlessly while I fumble for the right words.