Some years ago I was at the yoiyama (宵山) – or maybe the yoiyoiyama (宵々山), or even the yoiyoiyoiyama (宵々々山) – in any case, the eve of the Gion Matsuri (祇園祭), Kyoto’s most famous festival. I came across a traditional dance performance and took some pictures, one of them is the banner for this post. This summer I wanted to make a drawing with a Japanese theme and I selected that picture.

Before starting on the drawing, I felt I had to find out more about the dance. Most of what follows is taken from the page about Ryōō 陵王 on the Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System and the Japanese Wikipedia page about Ranryōō (蘭陵王), with some additional information from this New York Public Library blog article.

The legend

The most common interpretation of the dance is that it celebrates the victory of Prince Lanling (Ranryōō, 蘭陵王) of Pohai (北斉 , Manchuria) over the Zhou dynasty, around 550 A.D. He was a general named Gao Changgong who was given a fiefdom in Lanling, so he was also known as the Prince of Lanling.

The Prince of Lan Ling was one of the four most handsome men in ancient Chinese history. A masterful warrior, he led his army into battle and vanquished his foes while wearing a fearsome Ryōō mask to hide his beauty.

His most famous battle was the breaking of the siege of Jinyong (金墉, near modern Luoyang) in 564 A.D. Gao Changgong led only 500 cavalrymen and fought through an army of Northern Zhou, which was attacking the city with 100,000 soldiers. He fought his way to the gates the city, surprising the defenders. The soldiers of Jinyong didn’t recognize him, so he took off his helmet and mask. The soldiers in the city rejoiced at his arrival and their courage returned. They opened the gates and joined the battle outside the city. Soon the army of Northern Zhou was defeated. To celebrate the victory, the soldiers composed the famous song and dance “Prince Lanling in Battle” (兰陵王入阵曲).

The tradition

There are variations on the legend: some say that the prince wore the mask himself to frighten his enemies, others that his father’s ghost appeared wearing the mask. Others trace the dance back to the Eight Dragon Kings (hachidai ryuuou 八大竜王) of the Buddhist Lotus Sutra.

Following this latter tradition, folk festivals in Japan since the 13th century often incorporate the dance of Ran-ryou-ou as a rain prayer, as dragons are associated with water. This may partly account for the great popularity of the dance.

The dance

The dance is called ranryouou nyuujinkyoku (蘭陵王入陣曲) “The song of Prince Lan-Ling going into Battle”. It is a traditional Japanese court dance or bugaku (舞楽) introduced in the Japanese Imperial courts in the 9th century, and performed to traditional Japanese court music or gagaku (雅楽). For much of its history, bugaku was an exclusive and privileged experience, performed only at the Japanese imperial court and, very rarely, as part of religious rituals at temples or shrines.

In those days (the Heian era) the imperial court was organized with a strict Left and Right division. In terms of culture, poetry, music and dance, the Left was associated with China or India and the Right with Korea. Costumes for dances of the Left are primarily red. The music, tougaku (唐楽) is a Japanese adaptation of Chinese musical styles prevalent during the T’ang Dynasty.

The Ranryōō is a dynamic dance of the Left (sa-no-mai 左舞) and it is originally from either China or Southeast Asia (rin’yuugaku 林邑楽). It is performed by one person dressed in a fringed tunic and pantaloons (ryoutou shouzoku 裲襠装束).

The mask or bugakumen (舞楽面) is of a fierce, mythical golden beast with a dragon perched on its head.

The mask

Although Ranryōō masks can look vary different, they all share a common set of features: a sharp, long nose; bulging, rotating eyes (dougan 動眼); a gaping mouth with huge teeth and dangling chin (tsuriago 吊顎); wrinkles that line the face and the carved strands of heavy hair above the forehead. The golden face and metallic eyes are offset by the blue-green hair and vermilion mouth. There are tufts of animal hair suggestive of eyebrows, a moustache and beard. On the top of the head perches a crouching dragon. I found an interesting blog post (in Japanese) by a Ranryōō dancer, where he compares various masks from his own collection.

The drawing

I wanted to make a drawing with bright colours and a lot of detail, and also I prefer to draw human figures, but I didn’t want to do a portrait. So this Ranryōō dancer was a perfect match. I replaced the audience with people in yukata (浴衣, a light summer kimono) to make the scene more homogeneous. For most of the yukata designs I used my own pictures but the designs of the central four figures are based on the yukata worn by the sisters in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s wonderful movie “海街 diary” (“Our little sister”). The main focus is of course the dancer, so I drew and coloured the musicians and audience in a much more sketchy way.

The paper for this drawing is Arches 56cm x 76cm 300g/m2 “rough” watercolour paper. It’s a really nice paper with a pronounced grain and absorbs the water really well. As I did not tape it on a board, the sheet of course buckled a bit.

I used Derwent Inktense and Conté Aquaralle pencils as well as watercolour paint (various brands). The Inktense pencils give a very saturated colour. It was the first time I used them but I really like them.

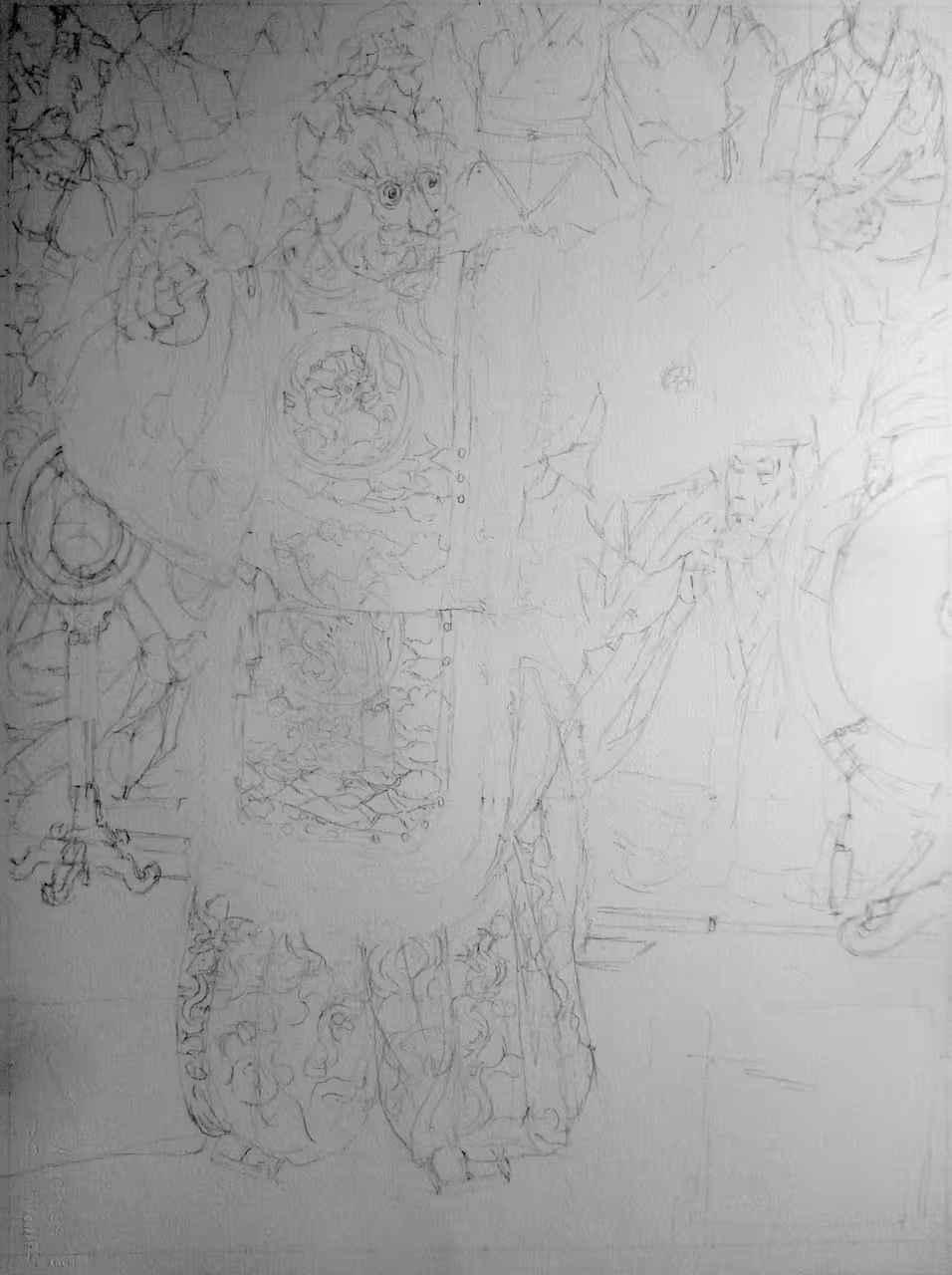

I started the drawing as usual with a pencil ghost drawing. Because of the size of the drawing, I used a grid to make sure the figure was positioned correctly.

Then I added a first layer of detail and colour with the watercolour pencils.

Next I started to detail and wash the mask. I needed a very fine pencil and a magnifying glass for the eyes.

Then I worked on the tunic in the same way.

Next I did the trousers, which took a long time, and the sleeves, ending the first full pass of the entire figure.

Then I worked on the detail of the yukata of the figures in the background, which I decided to do in indigo blue for all of them. Usually I use a relatively blunt pencil because in general that works better on coarse-grained paper, but to render the patterns on the fabric with very fine lines before washing them I used an extra-sharp pencil.

Next I added more detail and colour to the musicians, but I left them quite sketchy on purpose.

Then I put a second layer of colour on the dancer, to make the red and orange more vibrant, and make the shadows more pronounced. I used a mixture of watercolour paint and watercolour pencils.

Finally I did another pass of the entire drawing. I added more colour to the background figures but made them darker at the same time, as they are actually in the shadow. Adding the shadow layer was tricky because I could not just wash the entire background with a darker tint, as it would make the colours run. Instead, I used a layer of colour pencil. I added still more colour to the dancer, especially to the sleeves, again using a mixture of watercolour paint and watercolour pencils.

To finish the drawing I added a description in Japanese, “蘭陵王 雅楽公演 祇園祭”, which means “Ranryoo, public bugaku performance, Gion matsuri”.