In my previous post about learning Japanese I mentioned that I am very slowly reading a book (“1Q84” by Haruki Murakami) in Japanese. (It’s now July 2016 and I’ve finally finished the first volume!)

This post is about reading Japanese. I’ll give some tips on how to look up kanji and a few handy rules to simplify the reading process. I haven’t really encountered these tips and rules as such in my learning materials, so I thought they may be of interest to other learners as well.

The kanji conundrum

When learning to read in a language that uses an alphabet, you can simply look up any word you don’t know in a dictionary. Because of the use of kanji (漢字, Chinese characters), things are more complicated for the learner of Japanese. Words written in katakana or hiragana (the sets of about fifty characters used to write Japanese phonetically) are easy to look it up. But what to do with kanji? There are about two thousand kanji in general use. Learning them all takes a long time: in the Japanese school system, it takes nine years. Typically each kanji has several possible readings (pronunciation) and meanings. And knowing every meaning of every kanji does not mean knowing the meaning of words that use combinations of kanji.

Reading for learning

For me, reading for learning is different from ordinary reading. Normally, I read to understand the meaning of a text. When learning Japanese, I also want to learn the readings of the kanji I encounter and I want to practise recall of the kanji and compound words that I’ve already learnt.

Usually I make a first pass through a page of the text without looking anything up, trying to remember as much as possible, both readings and meanings, and to guess at readings and meanings of compound words where possible. Very often the context helps to guess at meanings, so I make sure to read enough text to get sufficient context. Then in a second pass I look up every kanji for which I don’t know either the reading or the meaning, and every compound word that I don’t know.

Looking up kanji

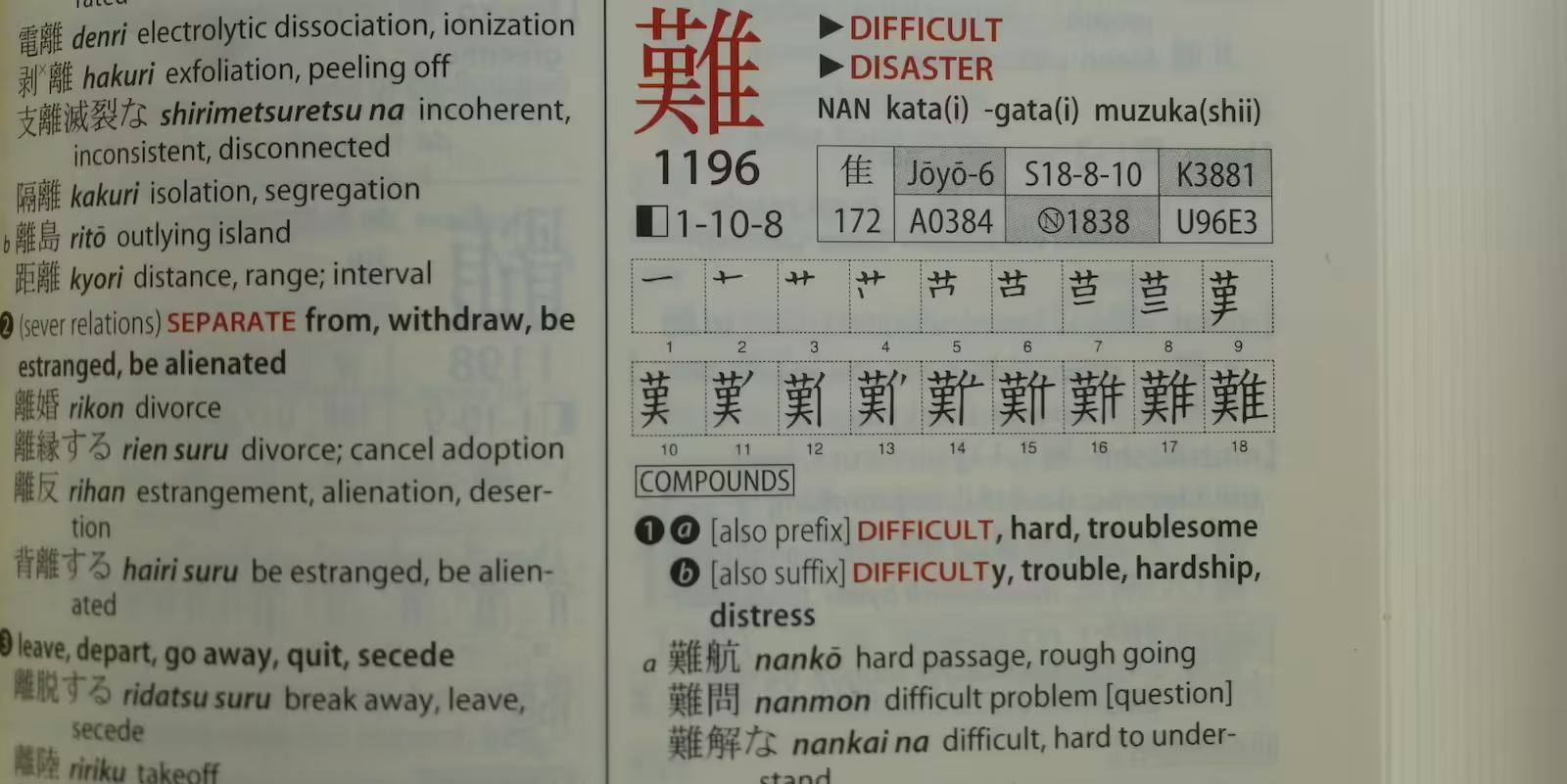

I find that the most convenient way to look up a kanji is an electronic dictionary on a smartphone, because I need to know just one of the readings. If I don’t know any of the readings, I use three different ways, depending on the kanji. All of them require understanding of the basics of kanji writing and structure: the stroke order, stroke count and the “radicals”, the kanji building blocks that make up the more complex kanji.

- The first way is to draw the kanji stroke by stroke. I prefer this approach as a learner, because I tend to remember the kanji better if I’ve had to write it. Typically, a kanji writing app will present a list of kanji that match the handwritten one. If my writing was good, I’ll get the kanji I was looking for on the first page.

- The second approach is to look up the kanji by radical. Most electronic dictionaries offer that facility. It usually works well if the radicals making up the kanji are clear. It really helps to know how to count the strokes in a radical, because they are usually ordered by stroke count.

- My final way is to use a (paper) dictionary with the SKIP (System of Kanji Indexing by Patterns) system for ordering kanji. I have the well-known “Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Dictionary”. The SKIP method is based on first classifying the kanji into one of 4 groups (Left-Right ◧, Up-Down ⬒, Enclosure ◻, and Solid ◼). For the first two categories, further indexing is by stroke count of both parts. Kanji in the third category (enclosure) are indexed by the number of sides of the enclosure. Kanji in the last category typically can’t always be broken down, but there aren’t that many of them and most of them are simple kanji.

Reading for learners: a few handy rules

Although the many readings and meanings may sound horribly complicated, I found that there are actually a few general rules that simplify the reading process. Of course there are exceptions to all of these rules but they hold most of the time.

Kanji have typically two types of readings, called on (音,”sound”) and kun (訓,”instruction” or “explanation”). The on-reading is based on the sound of the original Chinese reading of a character; the kun-reading is the Japanese word with the same meaning. Chinese used to play a similar role as Latin or Greek in ancient Japan, so in a way on-readings are comparable with words with a Latin or Greek root in English.

- The first general rule is that kanji appearing on their own (i.e. not in combination with other kanji) have almost always the kun-reading. For example, for the kanji 食, it will be one of the four kun-readings (く.う “ku-u”, く.らう “ku-rau”, た.べる “ta-beru” or は.む “ha-mu”), not one of the on-readings. To select the correct kun-reading, look at the hiragana following the kanji so 食う is pronounced as “kuu” and 食べる is pronounced as “taberu”.

- The second general rule is that in a compound word, all kanji have either the on- or the kun-reading. And for the vast majority of the compound words, it will be the on-reading. For example, 食事 is shokuji (on-on), not “ta-ji” (kun-on) or “shoku-koto” (on-kun). Generally, there are fewer on-readings than kun-readings for a kanji, and on-readings are also mostly single-syllable.

- Although there are indeed many on- and kun-readings, for most kanji one of each will be the most frequently used, and the others will likely be used only in fixed combinations.

- The same is true for meanings: usually one of the meanings is used much more frequently than all the others.

Even if reading a Japanese text may seem daunting at first, it is a very rewarding experience, and it is actually less complicated than it seems. I hope these tips and rules will help you to read Japanese more easily.