Tokyo Story (tōkyō monogatari, 東京物語) is a probably one of the most famous Japanese films, and definitely one of my favourites. It is a black-and-white movie from 1953 directed by Yasujirō Ozu about an elderly couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their grown-up children. It’s moving and poetic family story, slow-paced and without much overt drama. I very much like the cinematography, with long static shots of very carefully composed frames.

There is an article from the British Film Institute that provides a nice analysis of the movie and this article in FilmInquiry discusses the politics. The movie was released in 1953 and is quite critical of the Japanese society at the time.

There also is a very interesting article about the notion of time in this movie (in Japanese, abstract in French), “Recurrent time and irreversible time in Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story”. It explains how the parents, living in a traditional small village, experience time differently from the children living in the modern city, and how this is illustrated through the way time is handled in the movie.

Starting material

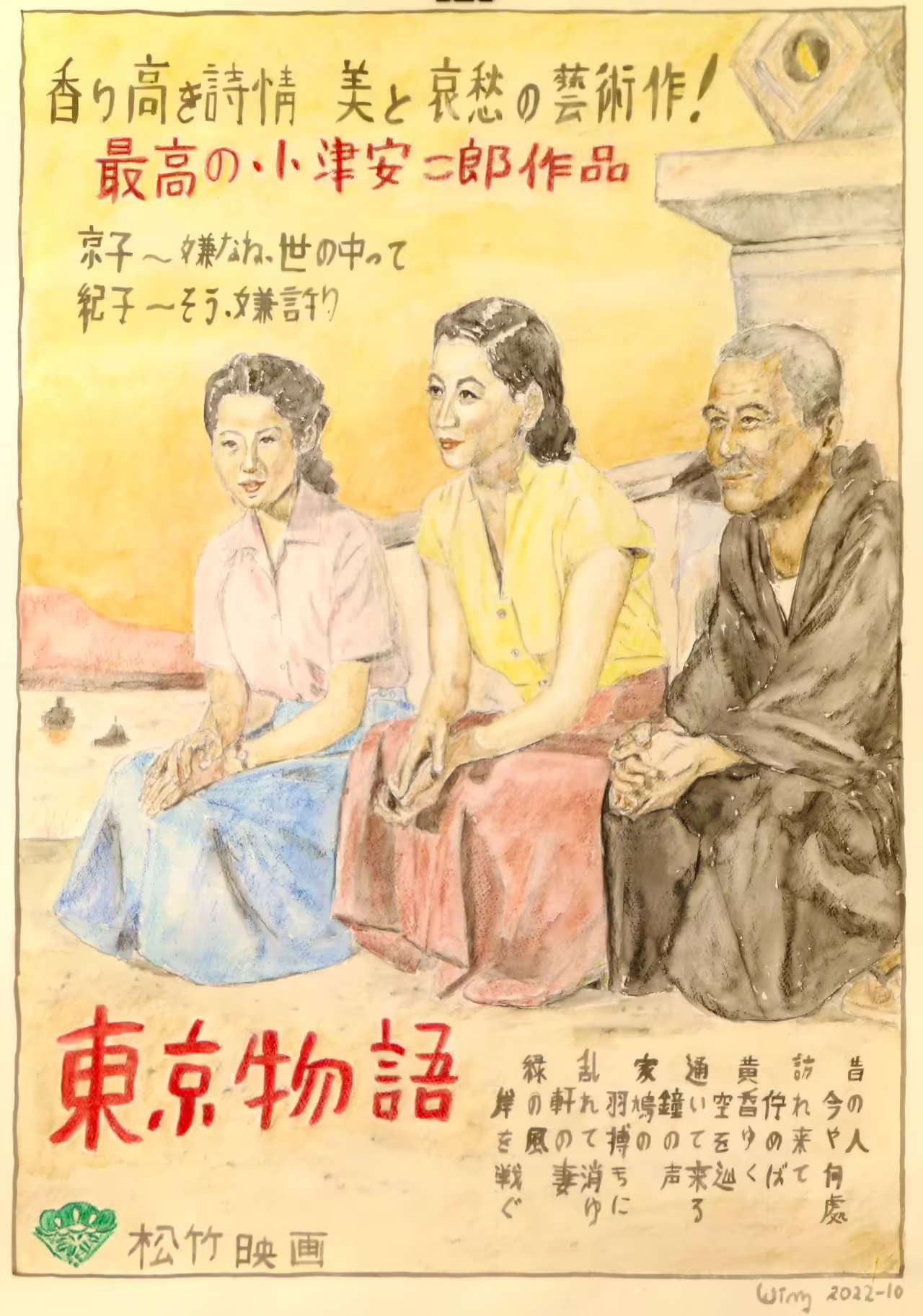

I wanted to make a drawing based on period posters for this movie. So I looked up a number of posters and composed a version with the three key figures of the final part of the movie, the father (Shūkichi), his daughter Kyōko and the widow of his son, Noriko.

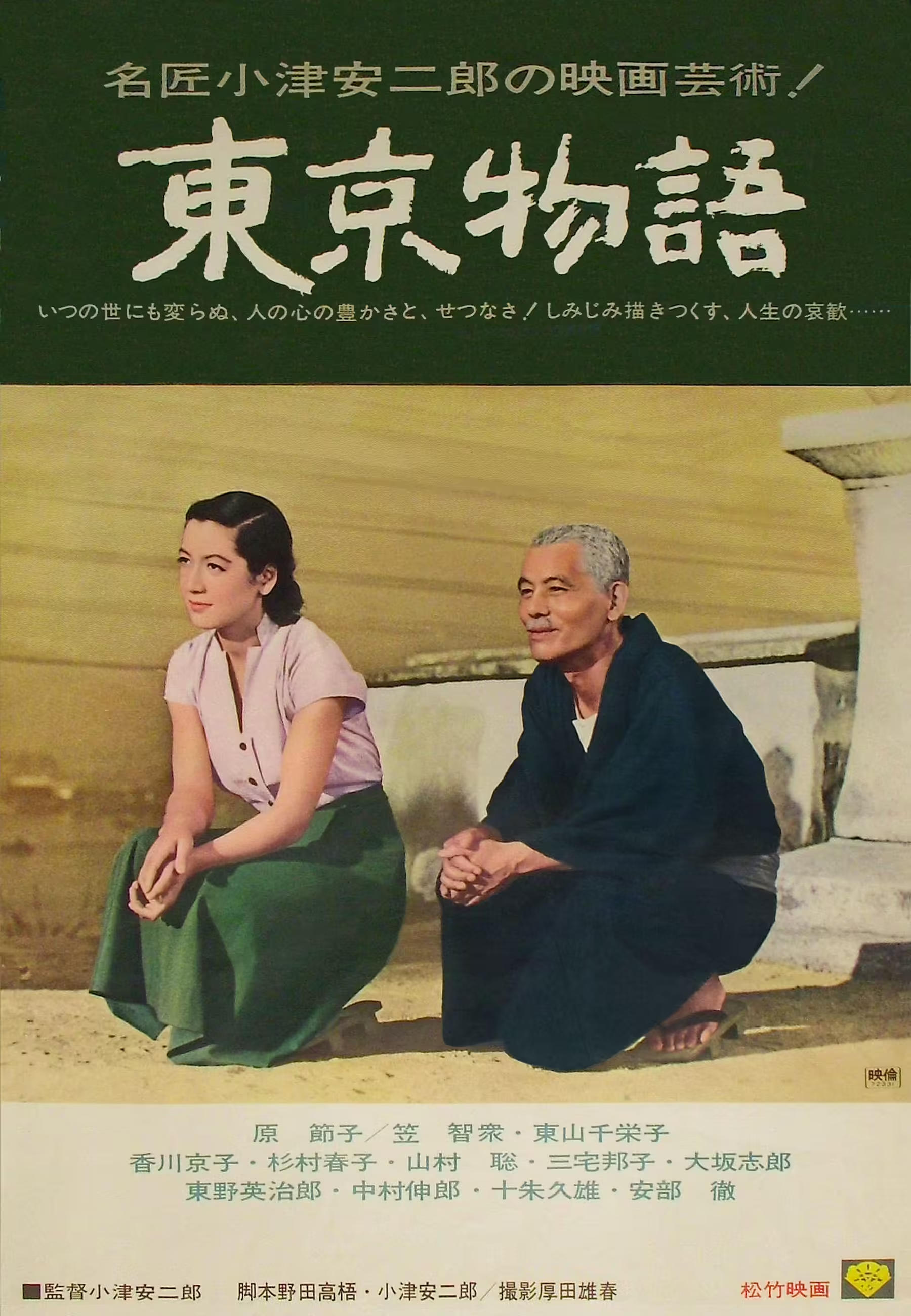

Here are the two posters I used:

Selecting the text

For a poster, the text is an essential part of the artwork. I wanted to keep some of the original promotion text but also add some that is taken from the movie itself.

The promotion text

Of course I kept the title, I used the lettering as in the first poster.

I kept the original line of one of the posters:

香り高き詩情 美と哀愁の藝術作

The first part means literally “fragrant poetic sentiment”, so maybe “a strong sense of poetry”; the second part means “a work of art of beauty and sorrow”.

I slightly modified another line from one of the posters:

一年一作小津安二郎作品

became

最高の小津安二郎作品

which means “Yasujirō Ozu’s best work”

The most memorable lines

I also incorporated what I consider the most memorable exchange in the movie:

For me this has always been the most memorable exchange in Tokyo Story. Noriko, the widowed daughter-in-law is talking to Kyoko, the younger daughter.

京子:「いやぁねぇ、世の中って……」

紀子:「そう、いやなことばっかり……」

The English subtitles translate this as

Kyoko: “Isn’t life disappointing?”

Noriko: “Yes, nothing but disappointment.”

“disappointment” is probably too strong though. いや (iya) is a term meaning disagreeable, unpleasant etc. 世の中 “yo no naka” means “world, society”, and the って means something like “what you call … “ or “the so-called …”

This is the conclusion of a longer exchange in which Noriko explains to Kyoko that it is inevitable that children drift apart once they have their own lives to live. I like this exchange because it summarizes what it means to grow up.

I stylised this a bit differently for the drawing:

京子〜嫌なね、世の中って

紀子〜そう、嫌な事許り

The evening bell

At the end of the movie, a children’s choir sings the song “The evening bell” (yuube no kane, 夕べの鐘) and I incorporated the lyrics into the poster as well:

昔の人

今や何處

訪れ来て

佇めば

黄昏ゆく

空を辿

通いて来る

鐘の声

家鳩の

羽搏きに

乱れて消ゆ

軒の妻

緑の風

岸を戦ぐ

I only incorporated the lyrics that are sung in the movie, there is a little bit more:

川のほとり

さまよえば

黄昏ゆく

路地を越えて

おとない来る

鐘の声

牧の童が

笛の音に

消えては行く

村はずれ

I have not seen any mention of this song in articles about the movie, and yet it is significant, because it describes an evening scene in a small village by a river, the kind of village where the father and daughter live.

I could not find a translation, I did my best to translate it but the song is from 1908 and besides being poetry, it uses some archaic constructions.

the people of yore, where are they now

maybe they loiter and come to visit

the gathering dusk creeps across the sky

the sound of the bell coming and going

vanishing eaves, disturbed

by the flapping of pigeon wings

the green wind stirring the bank

wandering around the river

dusk creeps across the paths through the fields

the sound of the bell comes to visit

a shepherd boy with the sound of a flute

fading away on the edge of the village

The background to the choice of this song in the movie is interesting. This was a song taught to school children before the war, but after the war, by the time the movie was made, it had been replaced by another song, “Spring breeze”, with the same melody but different lyrics. So why did Ozu choose this particular song? This song is much more serious in tone than Spring Breeze, it has something of a requiem or elegy.

I read an interesting story about the possible reason for this choice. Yasujiro Ozu’s assistant director, Yoshio Tsukamoto, died from leukaemia at the age of 39 shortly before the filming of the movie had started. They had been very close and had been through the war together, in Singapore. They were interned there after the war and when a ship came to repatriate them, there were not enough places. Ozu ceded his place but Tsukamoto stayed with him.

Ozu was deeply affected by Tsukamoto’s death, and this song was his way of expressing his grief in the movie.

This may have been the case but even without this personal background, the choice of the song is perfect for the final scene, cutting between Noriko in the train and Kyōko classroom. There is even a nice connection with the two notions of time: Noriko on the train steaming to Tokyo, looking at the watch signifying the irreversible time, and the temple bell in the song, which epitomises the recurrent time.

The drawing

The drawing process and the materials I used for this drawing are the same as for the drawings discussed in my previous posts, “The Blue Dragon of Kiyomizu-dera” and “Summer night in Shinbashi dōri”. This drawing is on a sheet of watercolour paper of 56 cm × 76 cm (30×22 inches) of Fabriano Artistico 300 g/m² “not”, cold pressed with a rough finish.

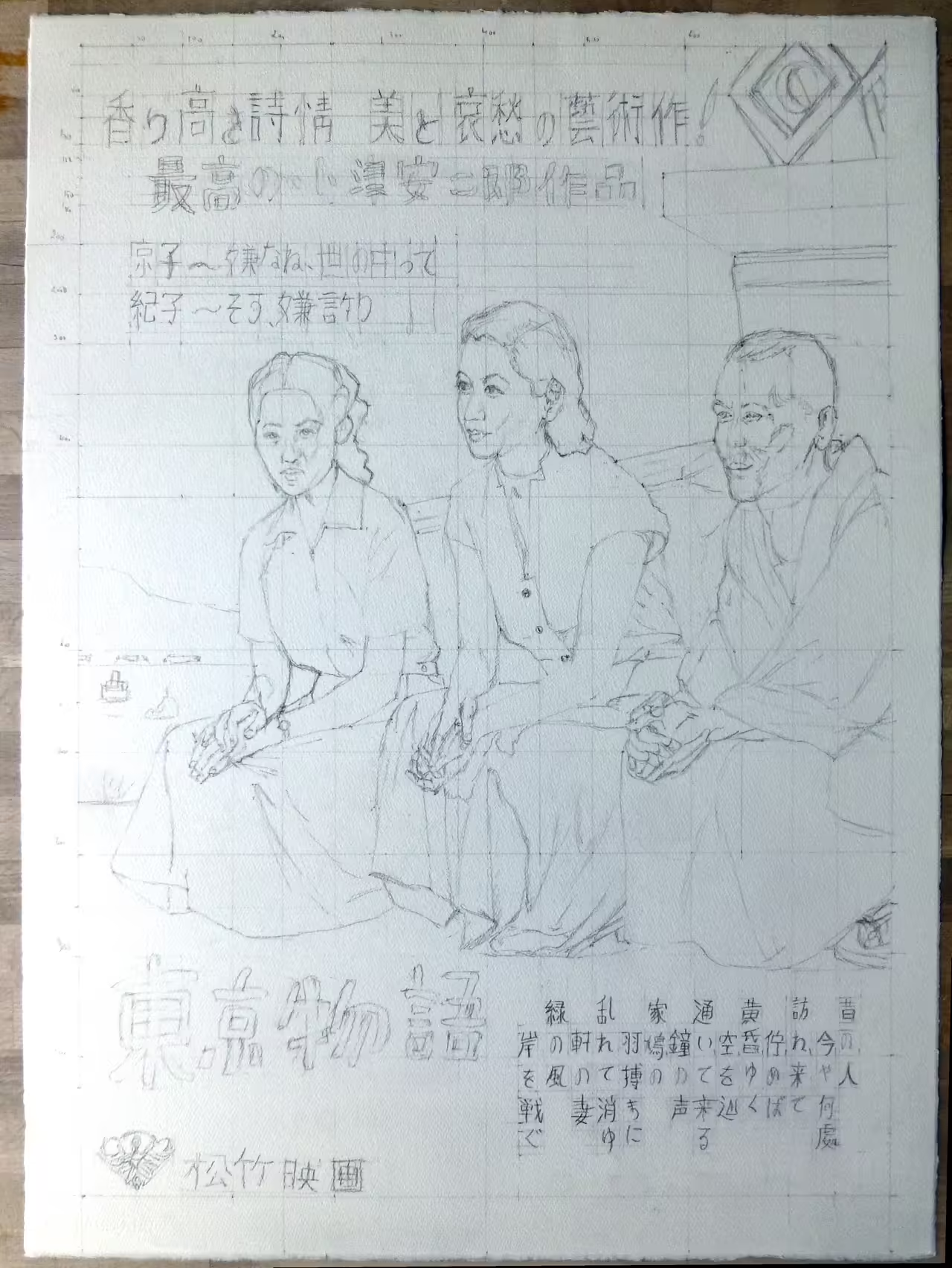

I only took one intermediate picture, of the the line drawing:

And this is the final result:

hiragana and romaji of the text

For learners of Japanese, here are the hiragana and romaji for the text on the poster.

The first line

香り高き詩情 美と哀愁の藝術作

かおりたかきしじょう びとあいしゅうのげいじゅつか

kaoritakaki shijou bi to aishuu no geijutsuka

The second line

最高の小津安二郎作品

さいこうのおつやすじろうさくひん

saikou no otsu yasujirou sakuhin

The dialogue

京子:「いやぁねぇ、世の中って……」

紀子:「そう、いやなことばっかり……」

きょうこ:「いやぁねぇ、よのなかって……」

のりこ:「そう、いやなことばっかり……」

Kyouko: iyaa nee, yo no nakatte…

Noriko: sou, iya na koto bakari…

The movie’s name

東京物語

とうきょうものがたり

tōkyō monogatari

The song

ゆうべのかね

むかしのひといまいずこ

おとずれきてたたずめば

たぞがれゆくそらをたどり

かよいてくるかねのおと

いえばとのはばたきに

みだれてきゆのきのつま

みどりのかぜきしをそよぐ

かわのほとりさまよえば

たぞがれゆくやろをこえて

おとないくるかねのおと

まきのわらべふえのおと

きえてはゆくむらはずれ

yuube no kane

mukashi no hito ima izuko?

otozure kite tatazumeba

tazogare yuku sora wo tadori

kayoite kuru kane no oto

iebato no habataki ni

midarete kiyu noki no tsuma

midori no kaze kishi wo soyogu

kawa no hotori samayoeba

tazore yuku yaro wo koete

otonai kuru kane not oto

maki no warabe fue no oto ni

kiete wa yuku murahazure

The banner picture shows a black-and-white picture of the father and his daughter-in-law in the same pose as on the poster.